Singapore – Revised sentencing framework for private sector corruption offences

-

2022年11月17日 2022年11月17日

-

亚太地区

-

Regulatory risk

In the recent case of Goh Ngak Eng v Public Prosecutor [2022] SGHC 254, the Singapore High Court took the opportunity to develop a sentencing framework for private sector corruption offences, declining to adopt the existing framework as set out in Takaaki Masui v Public Prosecutor and another appeal and other matters [2021] 4 SLR 160.

This article will explore the nature of this revised sentencing framework, and consider its impact on future cases.

Background

Sometime in late-2014, Goh Ngak Eng (“Goh”) was approached by Rajavikraman s/o Jayapandian (“Raj”), who indicated that he would be able to refer jobs from Keppel FELS (“KFELS”) to contractors. Raj stated that he knew Alvin Lim Wee Lun (“Lim”), a yard manager in the Facilities Department at KFELS, who was in a position to recommend to whom the jobs were to be awarded. Due to an administrative lapse in KFELS’s procurement process at the time, Lim effectively decided which contractors would be invited to quote for jobs and which would eventually be recommended to be awarded with jobs.

Subsequently, Goh conspired with Raj and Lim to obtain bribes amounting to almost S$880,000 from a number of KFELS’s vendors, including Spectrama Marine & Industrial Supplies Pte Ltd and Growa (F.E.) Pte Ltd, in return for causing KFELS to engage these contractors for the purposes of providing equipment and/or services. In addition, Goh also paid bribes to Raj for the latter’s company to award works to Goh’s company Megamarine Services Pte Ltd, and to one Ong Tun Chai to falsify invoices in furtherance of the aforementioned conspiracy involving KFELS.

Goh pleaded guilty to a total of 19 charges, comprising 15 charges of abetment by engaging in a conspiracy to corruptly obtain gratification and 4 charges of corruptly giving gratification, with another 40 charges under the Prevention of Corruption Act (Cap 241, 1993 Rev Ed) (“PCA”) taken into consideration for the purpose of sentencing. In the court below, the District Judge imposed a global sentence of 17 months and 3 weeks’ imprisonment. Dissatisfied, Goh appealed against the sentence imposed as being manifestly excessive.

Issues before the High Court

On appeal, the 4 issues before the Singapore High Court were as follows:

- should the existing sentencing framework in Takaaki Masui v Public Prosecutor and another appeal and other matters [2021] 4 SLR 160 (“Masui”) be followed, or should a revised sentencing framework be developed;

- should the revised sentencing framework extend to private sector corruption offences under Section 5 of the PCA as well as cases of public sector corruption;

- if a revised sentencing framework ought to be developed, what offence-specific factors should be included and what would be the indicative sentencing ranges; and

- if the sentence imposed on Goh was manifestly excessive and whether it ought to be reconsidered.

Decision of the High Court

The Singapore High Court held that:

- the sentencing framework in Masui ought not to be followed, as it was “excessively complex and technical, making it prone to confusion and uncertainty and therefore rendering it of limited assistance”. As such, a revised sentencing framework based on the two-stage, five-step framework (the “Revised Sentencing Framework”) in Logachev Vladislav v Public Prosecutor [2018] 4 SLR 609, should be adopted;

- the Revised Sentencing Framework should not be extended to offences under Section 5 of the PCA, or to cases of public sector corruption; and

- the sentence imposed on Goh ought to be enhanced, notwithstanding that the prosecution did not file a cross-appeal against the sentence imposed. As such, the High Court proceeded to impose a global sentence of 37 months and 3 weeks’ imprisonment.

The Masui Framework

By way of background, the Court in Masui had introduced a five-step sentencing framework, comprised of the following steps:

- Step 1: the court will identify and assess the relevant offence-specific factors present on the facts of the case based on the two broad sentencing parameters of harm and culpability.

- Steps 2 and 3: the court will derive an indicative starting sentence through the application of the “Modified Harm-Culpability Matrix” and “Contour Matrix”. These are fairly complicated matrices that set out a range of indicative starting imprisonment sentences depending on the level of harm caused by the offence and the level of the offender’s culpability.

- Steps 4 and 5: the court will consider all offender-specific factors to derive a sentence for each individual charge, and ensure that the aggregate sentence is sufficient and proportionate to the offender’s overall criminality.

However, the Singapore High Court in this case considered that Steps 2 and 3 of the Masui framework were “excessively complex” and rendered the framework “unworkable for sentencing courts to apply” noting, inter alia, that the identification of an indicative starting sentence was not a mathematical exercise.

We now turn to consider the Revised Sentencing Framework, the offence-specific factors to be considered, and the indicative sentencing ranges, as determined by the High Court.

Revised Sentencing Framework

The Singapore High Court held that the sentencing framework to be adopted should instead be based on the two-stage, five-step framework in Logachev Vladislav v Public Prosecutor [2018] 4 SLR 609, and therefore approved the revised sentencing framework set out below:

- First Stage: At the first stage of the framework, the court arrives at an indicative starting point sentence for the offender which is reflective of the intrinsic seriousness of the offending act.

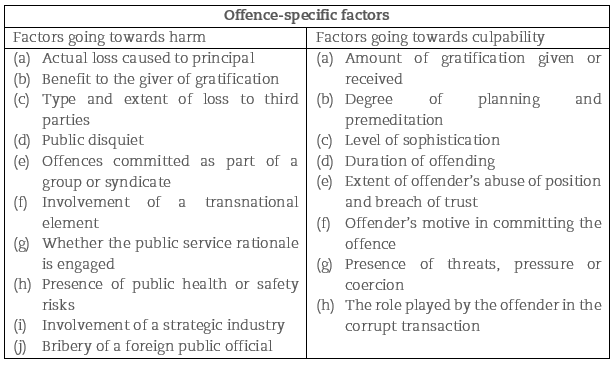

- Step One: By reference to factors specific to the particular offence in question, the court identifies the level of harm caused by the offence and the level of the offender’s culpability. These factors are set out below:

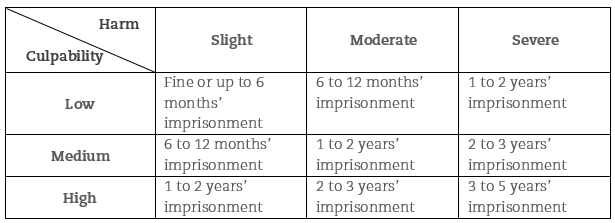

- Step Two: By reference to the level of harm caused by the offence and the level of the offender’s culpability, the court identifies the applicable indicative sentencing range. The indicative starting sentences for an accused person who is convicted after trial for offences under sections 6(a) and (b) of the PCA are set out in the following sentencing matrix:

- Step Three: The court identifies the appropriate starting point within the sentencing range identified in Step Two, by considering the specific details of the case with reference to the same offence-specific factors considered in Step One.

- Second Stage: At the second stage, the court may make adjustments to the starting point sentence identified in the First Stage so as to arrive at a sentence that reflects the individual circumstances of the offender, and ensure that the overall sentence imposed is proportionate and consistent with the overall criminality of the offender.

- Step Four: The court makes such adjustments to the earlier-identified starting point sentence so as to account for offender-specific aggravating factors (such as other offences taken into consideration for sentencing purposes) and mitigating factors (such as cooperation with the authorities).

- Step Five: Where an offender has been convicted of multiple charges, the court will consider if further adjustments should be made to the sentence for the individual charges so as to ensure that the overall sentence imposed is sufficient and proportionate to the offender’s overall criminality.

Scope of Revised Sentencing Framework

The Revised Sentencing Framework will apply to private sector corruption offences under Section 6 of the PCA, but not be extended to private sector corruption offences under Section 5 of the PCA and cases of public sector corruption. The different sections of the PCA are directed at distinct mischiefs and therefore will engage different considerations in the sentencing exercise.

Comment

This decision represents a notable departure from the Masui framework, known for its portrayal by way of 2-dimensional and 3-dimensional conceptual diagrams and models, and provides welcome clarity as to the approach to be taken by sentencing courts in relation to private sector corruption offences.

Furthermore, this decision reflects the Singapore judiciary’s recognition of the importance of deterrence in tackling corruption in the private sector. Indeed, the High Court had noted that the need for deterrence had resulted in a recent upward trend in custodial sentences for serious private sector corruption, and that sentences imposed in analogous historical cases may no longer serve as suitable reference points.

This position was exemplified by the High Court’s refusal to restrict the indicative sentencing range for a case of slight harm/low culpability to only a fine (thereby including a custodial term of up to 6 months), in developing the Revised Sentencing Framework. Furthermore, it is also noteworthy that the High Court had exceptionally enhanced Goh’s sentence on appeal by more than twofold, notwithstanding that the prosecution did not appeal against the original sentence imposed.

Should you require any assistance with or support on regulatory and investigation matters, our team would be happy to assist. Please do not hesitate to contact Tan Weiyi or Jeffrey Koh.

结束