A Global Snapshot – The Regulatory Exposure Landscape for Professional Firms

-

Étude de marché 31 juillet 2024 31 juillet 2024

-

Global

-

Réformes réglementaires

-

Réglementation et enquêtes

As practice protection lawyers, we have witnessed regulatory exposures for professional services firms rise steadily up the risk radar to become a risk that is at least equal to, if not higher than, the threat of a civil claim. As with liability claims, the global landscape is not uniform, but a heightened risk of regulatory scrutiny has become a recurrent theme.

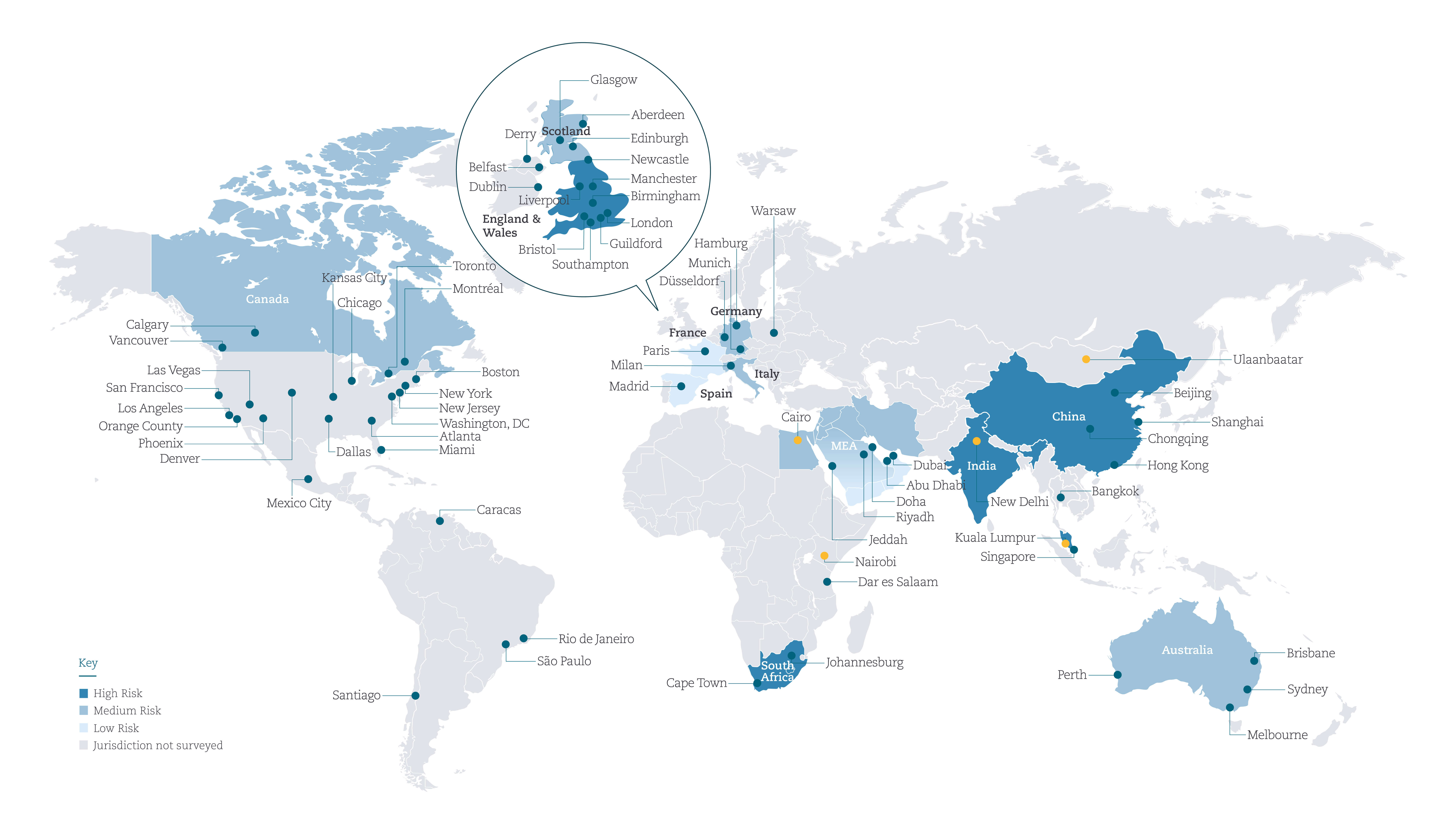

The current picture

Our professional services firms risk heatmap for 2024, compiled across our practice, reveals that of the 13 jurisdictions included, regulatory scrutiny and enforcement was graded at least a medium risk in 11 of those jurisdictions, with our lawyers in England and Wales, China, Singapore, South Africa, and India grading the threat as high.

The factors that lead to this assessment include the strength of the regulatory framework in place, how active/aggressive the regulators are in policing professional firms, and the sanctions regime. In recent years we have seen regulators across jurisdictions become more international in their outlook, become increasingly active and better resourced, with higher expectations of cooperation, and with fines on an upward trajectory. Even for those jurisdictions in which a regulatory framework for professionals is relatively recent (such as the Middle East), the direction of travel for regulatory exposures is only one way.

The factors that lead to this assessment include the strength of the regulatory framework in place, how active/aggressive the regulators are in policing professional firms, and the sanctions regime. In recent years we have seen regulators across jurisdictions become more international in their outlook, become increasingly active and better resourced, with higher expectations of cooperation, and with fines on an upward trajectory. Even for those jurisdictions in which a regulatory framework for professionals is relatively recent (such as the Middle East), the direction of travel for regulatory exposures is only one way.

Across our practice, we have witnessed the emergence of several global themes:

Increasing globalisation of investigations

Within the financial services context, the LIBOR and forex-fixing investigations witnessed multiple regulators, across different jurisdictions, seeking to impose fines on a single firm. These investigations bore witness to an unprecedented rise in cooperation between international regulators.

Regulators have for some years now been cooperating on a much greater level, particularly those tasked with stamping out bribery and corruption in the context of enforcement. For example, 2017 saw the results of investigations undertaken by authorities in the US, Brazil, and Switzerland into allegations against Odebrecht (Brazil’s largest construction firm). The ability to investigate and take appropriate action was made easier by the global sharing of information and resources.

Competing and conflicting regulatory and legal regimes have also led to difficulties, for instance over access to documents held by large accounting firms which might, if disclosed, cause those firms to be in breach of their legal obligations in other jurisdictions (e.g. the so-called French "blocking statute"). Audit working papers in China for example cannot be transferred outside of the Mainland unless PRC authorities give approval.

In the Middle East, some jurisdictions, such as Bahrain, make it a criminal offence to share certain corporate information outside the country. Generally, professionals such as auditors also face criminal risks for sharing client information, but where they are required to do so by a foreign court or regulator, that can leave them in a very difficult quandary.

At the same time, entities and professionals must also grapple with the increasing amount of legislation that has extra-territorial reach, such as the various UK statutes dealing with bribery, criminal finance and modern slavery, and the resurgent use in the US of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (‘FCPA’), the effect of which is to require entities to increase due diligence across the supply chain.

The importance of whistleblowers

Recognising the importance of whistleblowers in uncovering wrongdoing, the EU has recently legislated to give greater protection to whistleblowers through the EU whistleblowers directive, and the UK government is currently consulting on enhancements to its own regime. Other Jurisdictions such as the US, France, and Italy provide specific protection to whistleblowers, and other jurisdictions such as Germany have begun introducing whistleblower provisions related to the financial sector.

Where regulatory enforcement is, or is perceived to be weak, whistleblowing is often the reason that problems come to light. A case in point is the Middle East, where, recognising their importance in combatting fraud, new regimes have been put in place in the offshore regimes (DIFC and ADGM). However, there is no culture of whistleblowing, and, indeed, defamation is also a criminal offence, making it a high-risk strategy to turn on an employer or any third party (even if the disclosures are true).

Cooperation and coverups

We have seen a number of cases where professional firms have been sanctioned by the regulator in relation to attempts by individuals within the firm to cover up mistakes and/or mislead the regulator. Such cases are a salutary reminder about the risks of acting in a way that makes a bad problem worse, given the indications that severe sanctions can ensue. Clearly, the firm’s conduct once the cover-up is discovered will be important, and self-reporting and co-operation with any subsequent investigation and enforcement process will be mitigating factors. Although there are not enough cases to warrant conclusions about trends, it appears to us likely that an individual covering up their own mistake will likely attract a less severe sanction than a cover-up that is endemic within a firm. The regulatory sanctions meted out for cheating in professional examinations administered by firms illustrate some of the issues that can arise; driven by US regulatory action against US firms, this has spread to firms based in Canada, Australia, and a variety of other jurisdictions. One UK firm has now been sanctioned by the US regulator. The very large range of fines imposed for similar-sounding underlying behaviour, from under USD1m to USD100m, could be explained by the degree of perceived “cover-up” in terms of prompt self-report and co-operation with the regulatory process; or, alternatively, finding a way to set a very high “signalling” precedent.

Politicisation

Regulation is becoming increasingly politicised, impacting the approach of regulators in a number of countries.

One example of politicisation, which has played out through regulatory enforcement with uncomfortable consequences for the accountancy firms, has been the protection disputes between the Chinese, US, and Hong Kong authorities over the historic inability of the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) in the US to conduct inspections and investigations of Chinese auditing firms.

Another aspect of politicisation is the distinct rise in enquiries by parliaments and parliamentary committees. Such political enquiries commonly lack the procedural safeguards that would apply in a formal regulatory enquiry or civil claim, resulting in a more uncontrolled and unfocussed process for professionals, with the ever-present reputational risk of how it plays in the media.

The following are illustrations:

- In the UK, an array of accountants and lawyers were called to give evidence in parliament in relation to the BHS and Carillion matters, mentioned above.

- Recent years have also seen various forms of political/parliamentary bodies question auditors over relationships with entities/persons involved in corporate collapses/corporate or public figure wrongdoing in Spain, the Netherlands, and South Africa.

Political scrutiny can also shape regulatory agendas. For example, there has been considerable political and media attention prompted by concerns about Russian oligarchs’ use of the English courts and latterly by the use of ‘SLAPP tactics’ (strategic litigation against public participation; actions intended to thwart critics by burdening them with legal defence costs) on behalf of public figures facing scrutiny. This has led directly to an active focus of the lawyers’ regulator (SRA), who said they were investigating 50 such cases in November 2023.

Professionals as arbiters of corporate behaviour

Heightened public sensitivity has also led to an increasing characterisation of professionals as ‘enablers’ of poor corporate behaviour. A clear example is the debate over tax planning, in which professionals have been castigated in the media by regulators and by the courts. In a number of jurisdictions, there has been intense public and media scrutiny of tax planning, blurring the line between avoidance and evasion. This has been fuelled by public scandals such as the Panama and Paradise Papers, which reverberated globally. Current areas of regulatory focus include tax advisor misconduct in Australia, and involvement in corruption and state capture by lawyers and accountants in South Africa. In the UK, the recently enacted Economic Crime and Corporate Transparency Act 2023 gives the SRA the power to issue unlimited fines in certain circumstances, as well as enhanced powers to demand information/documents relating to the prevention or detection of economic crime and makes ‘promoting the prevention and detection of economic crime’ a regulatory objective for legal regulators including the SRA.

Blurring of the professional/personal divide

Lastly, over the last couple of years we have seen a blurring of the distinction between professional and personal matters when considering what amounts to misconduct by accountants and lawyers in the UK. This reach into the personal lives of professionals has profound implications for professionals with a risk of regulatory “overreach”.

The implications of heightened regulatory exposures

Regulatory exposures can be costly and time consuming to defend, with financial and other sanctions as well as a range of important business and reputational consequences. However, significantly, regulatory action has the effect of complicating, and worsening the related civil claims which increasingly run in parallel with regulatory problems. Following the collapse of Wirecard, for example, its auditors faced regulatory action from Germany’s auditor oversight body, APAS, in addition to a number of civil suits from disgruntled shareholders.

We have also seen an increase in the “weaponisation” of regulatory complaints; the bringing by claimants (including insolvency practitioners) of a regulatory complaint in order to obtain information for use in civil litigation in the UK and liaising with regulators to “assist” their enquiries. This “entrepreneurial” approach to civil litigation is not new in the professional sphere, but we are now starting to see these tactics deployed in relation to claims in larger numbers.

Comment

The increased globalisation of regulatory investigations coupled with the more prominent role of whistleblowers, the danger associated with cover ups, increased political scrutiny and a sometimes-negative public perception of some professions linked to poor corporate behaviour, all point to the need for professional services firms to remain acutely aware of the increasingly complex terrain of regulatory risk and to carefully prepare to remain ahead of the curve.

Fin