Liability risks for D&Os in connection with ESG regulation

-

Insight Article 31 October 2024 31 October 2024

-

UK & Europe

-

Climate change

-

Dispute Resolution

Environmental, social and governance (ESG) issues have become significantly more important in recent years. Natural disasters and their consequences, such as business interruption, climate change and the associated climate lawsuits, as well as increasing regulation in this regard, are among the most significant business risks that insurers and their customers face today and will face in the future. [1]

1. Climate Change Litigation

The number of legal disputes related to climate change and its effects, often referred to as “climate change litigation”, is continuously increasing and has more than doubled since the signing of the Paris Agreement in 2015. [2] While the majority of the lawsuits are (still) directed against governments, plaintiff (associations) are increasingly focussing on companies and are acting more and more professionally. Although most predominantly, the United States are in the focus of climate change litigation worldwide, climate litigation in Europe and Germany is on the rise. The subject matters in climate change litigation range from the assertion of so-called climate damages to the review of emission credits, lawsuits for the reduction of greenhouse gases, the tightening of national climate protection laws, and the omission of misleading advertising (“greenwashing”). [3] In addition to the proceedings against the German automotive industry, the action for proportional damages brought by a Peruvian farmer and the rulings of the Higher Administrative Court of Berlin-Brandenburg in connection with the German government’s Climate Protection Act, the judgment of the European Court of Human Rights on the rights of the “KlimaSeniorinnen Schweiz” [4] and the Federal Court of Justice’s appeal decision on misleading advertising for fruit gums using the term “climate-neutral” [5] received a great deal of media attention.

2. ESG regulation

This increase in climate lawsuits is accompanied by progressive ESG regulation. The abbreviations SFDR, TNFD, CSRD, ESRS, CSDDD [6] and many more are emblematic of the new set of requirements for German board members and managing directors. This article focuses – more due to limitations of scope than to an assumed and actually non-existent hierarchy – on the German and European regulations on due diligence obligations along the (international) supply chain and on the proposal for a Green Claims Directive adopted in March of this year, which is currently in the European legislative process.

3. Liability risks for managing directors

As a consequence of the increasing number of legal actions against selected companies – which, in addition to the omission of behaviour that is harmful to the climate, are already occasionally aimed at condemning the companies to pay compensation – and the progressive ESG regulation, the liability risk for board members and managing directors in Germany is also increasing – and with it the potential risk exposure of their D&O insurers.

Regulation of due diligence along the supply chain

1. The Supply Chain Due Diligence Act

The German Supply Chain Due Diligence Act (Lieferkettensorgfaltspflichtengesetz, LkSG) has been in force since 1 January 2023, making it one of Europe’s pioneers. On 1 January 2024, the scope of application was expanded to include companies that regularly employ at least 1,000 people in Germany. Ultimately, the Supply Chain Due Diligence Act regulates corporate responsibility for compliance with human rights and, to a certain extent, environmental protection in global supply chains. The individual due diligence obligations are regulated in more detail in Sections 3 et seq LkSG, which range from the establishment of a risk management system to ensure compliance with due diligence obligations – in order to identify and minimize human rights and environmental risks – to documentation and reporting obligations. The law provides for sanctions including fines, which for companies with an average annual turnover of more than EUR 400 million can be up to 2 percent of the average annual turnover. This could lead to fines of at least EUR 8 million for the company.

2. The Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive

For a long time, it was unclear whether or when the European counterpart to the German Supply Chain Due Diligence Act, the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (“CSDDD”, or also referred to as “CS3D”), would be adopted. After a long political struggle, European legislators approved the draft CSDDD in spring 2024, which then came into force on 25 July 2024. Germany and the further EU member states must now implement the CSDDD into national law within two years, by 26 July 2026.

In Germany, this is likely to be done by amending the Supply Chain Due Diligence Act. In light of this, the responsible board members should address new regulations and possible changes regarding due diligence in their supply chain at an early stage.

a) Scope of application

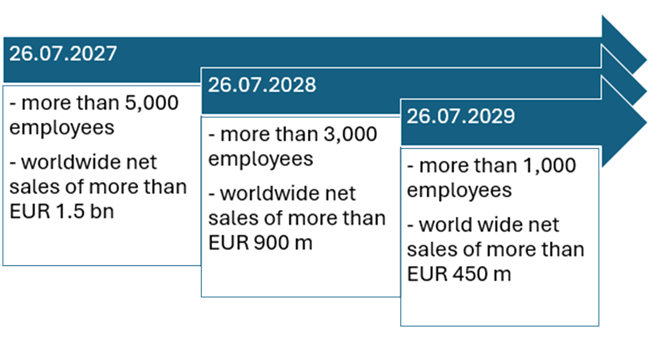

According to Art. 37 of the CSDDD, the new regulations apply to the following companies in a phased manner over time, with the scope of application being gradually extended:

b) Due-diligence obligations

Reference point for the company’s due diligence obligations under the CSDDD is the so-called “chain of activities”. The companies covered by the CSDDD are obliged to determine whether there are any human rights or environmental risks in this chain of activities and, among other things, to take appropriate preventive and remedial action. An overview of the individual due diligence obligations can be found in Art. 5 CSDDD, which is similar to the due diligence obligations regulated in the German Supply Chain Due Diligence Act. However, the CSDDD goes further than the German Supply Chain Due Diligence Act in several aspects, for example, in including indirect suppliers in the companies' program of obligations or regarding compliance with environmental obligations in general.

Pursuant to Art. 22 CSDDD, the company is obliged to mitigate climate change. It requires member states to ensure that companies adopt and implement a climate change mitigation plan to ensure that they do everything within their power to align their business model and strategy with the transition to a sustainable economy and the limitation of global warming to 1.5°C and the goal of achieving climate neutrality (as provided for in Regulation (EU) 2021/1119), and in which they specify their interim climate targets and the goal of climate neutrality by 2050, as well as, if necessary, the company's involvement in activities related to coal, oil and gas. It remains to be seen how the German legislator will implement this obligation, which arguably does not relate solely to supply chains but is of broader significance.

c) Sanctions and civil liability

With regard to sanctions, Art. 27 CSDDD provides, among other things, for administrative fines against companies of up to at least 5 percent of the company's worldwide net turnover. However, the new civil liability standard in Art. 29 CSDDD is likely to be particularly relevant for companies and their managing directors, which has not previously existed in this form – at least not in the German Supply Chain Due Diligence Act (see Section 3 (3) LkSG) – and will therefore be enacted by the German legislator for the first time in the course of implementing the CSDDD.

Art. 29 CSDDD establishes liability for companies if they intentionally or negligently violate the obligations under Art. 10 or Art. 11 CSDDD. These obligations are to prevent potential adverse impacts and to remediate actual adverse impacts on the environment or human rights. With regard to causality, Art. 29 para. 1 CSDDD provides that a company cannot be held liable if the damage was only caused by its business partners in its chain of activity. In practice, there is likely to be a lot of discussion in the future about when damage can be “solely” attributed to a business partner. If the requirements of the liability standard are met, the injured party has a right to full compensation for the damage (Art. 29 para. 2 CSDDD). The CSDDD also contains provisions on evidence, limitation periods and procedural costs. Overall, it therefore remains to be seen how the German legislator will implement the requirements of the civil liability standard under the CSDDD. However, it is already certain that the liability risks of companies and thus also for their managing directors and consequently D&O insurers will increase.

The Green Claims Directive [7]

In view of the increased importance of sustainability, environmental and climate protection for society as a whole, “green advertising claims” (so-called “green claims”) are also increasing. In order to protect consumers – and competitors – from the greenwashing that is sometimes associated with the “green claims”, the European Commission initially adopted a proposal for a directive, the so-called Green Claims Directive, in March last year, which the European Parliament approved with various amendments in March this year. This proposal is currently being discussed by Council of the European Union before it is presented to the European Parliament again for approval.

1. Objective

The aim of the directive is to ensure that only companies that have actually verified their “green claims” as environmentally friendly can also derive commercial benefits from using the “green claims”. To protect consumers and competitors from the associated greenwashing, the Green Claims Directive aims to implement a Europe-wide uniform and transparent standard regarding manufacturer information. In addition to protecting competition, this should also strengthen trust in green claims and labels and give consumers the opportunity to make informed and environmentally friendly decisions.

2. Scope of application

The scope of the Green Claims Directive includes all so-called larger companies that explicitly use “green claims” or “environmental labels” in connection with business practices vis-à-vis consumers. Micro-enterprises will be supported by a later start date of the new obligations and supportive measures such as training and funding from the European Commission. The directive applies, in principle, to all consumer products sold in the European Union. However, exceptions apply to products covered by existing European Union legislation.

3. Key elements

Before green claims can be used in advertising, they must in future be substantiated on the basis of scientific findings and independently verified. The Green Claims Directive contains specific requirements for this, which are intended to ensure that the product actually lives up to the proclaimed positive environmental impacts. To this end, a scientifically sound and state-of-the-art life cycle analysis of all significant environmental impacts is required – at the company's expense. This must demonstrate that the environmental aspects or environmental performance described in the “green claim” are actually significant in relation to the life cycle. It must also be decided and verified whether the “green claim” refers to the entire product or only to individual components, whether it applies to the entire life cycle or only to certain phases, and whether the “green claim” applies to all of the producer’s activities or only to certain parts.

In addition, companies falling under the scope of the Green Claims Directive must provide transparent information on the extent to which the product performs significantly better than usual in terms of environmental aspects, whether these positive environmental improvements lead to deterioration in other areas, and to what extent greenhouse gas compensation is implemented. If comparative situations arise, the company must use equivalent representative information or data for the assessment, or collect data in the same way as for the compared products.

Following their own scientific analysis, companies must then have the admissibility of their advertising with green claims verified by an independent, officially accredited body, which is then to decide on the issuance of a certificate of conformity. Once the certificate of conformity has been issued, it is valid throughout the entire European single market.

4. Sanctions

Companies that fail to provide the required evidence for green claims face various sanctions. In addition to a levy on the profits made from the sanctioned products, there is the possibility of excluding companies from public tenders and subsidies for up to twelve months. Furthermore, companies that violate the provisions of the Green Claims Directive could be subject to fines of at least four percent of the company’s global annual turnover. Finally, the directive explicitly allows qualified entities to bring representative actions to protect the collective interests of consumers.

5. Legal consequences under the German Act against Unfair Competition

The sanctions based on the Green Claims Directive apply in addition to the relevant national provisions of the German Act against Unfair Competition (Gesetz gegen den unlauteren Wettbewerb, UWG). Accordingly, false “green claims” may constitute misleading commercial practices (cf. Sections 3 para. 2, 5 para. 1 UWG). The sanctions provided for by competition law include the assertion of claims for removal and injunctive relief (cf. Section 8 UWG), claims for damages by competitors (cf. Section 9 UWG) and the possibility of skimming off profits (cf. Section 19 UWG).

In connection with misleading advertising, the Federal Court of Justice recently ruled that the term “climate-neutral” can constitute a misleading commercial act in accordance with Sections 3 para. 1, 5 para. 1 UWG if the meaning of such ambiguous term is not already explained in the advertisement itself. [8] The product, in this case fruit gums, had not been produced in a CO2-neutral manner, as only climate projects were supported to offset the CO2 emissions of the production. However, since the term “climate-neutral” could also be understood as “CO2-neutral” due to its ambiguity, an explanation in the advertisement itself was necessary to avoid misunderstandings on the part of the consumer. [9] The court took the defendant to court for an injunction under Section 8 para. 1 UWG.

D&O liability

In principle, liability risks for managing directors can always arise when a law or directive provides for sanctions in the form of fines – which is the case under the Green Claims Directive or CSDDD (as well as the German Supply Chain Due Diligence Act). This is because there is currently no ruling of the Federal Court of Justice in Germany on whether a company can recover fines imposed on it from its managing director in the event of a breach of duty under liability provisions pursuant to sections 93 para. 2 German Stock Corporation Act and 43 para. 2 German Limited Liability Companies Act. In practice, this is therefore an often-observed consequence of corporate fines. Unless there is an explicit exclusion in the D&O insurance general terms and conditions, D&O insurers must therefore also prepare for an increasing risk exposure in connection with the current regulatory efforts in the EU.

In addition, however, there are also an increasing number of liability risks under civil law. Although the current climate lawsuits against companies have not yet been successful[9], if a court were to award damages to climate plaintiffs in the future, such a judgment would have an enormous impact and would likely mobilize further plaintiffs. Therefore, managing directors should already be dealing with how to avoid climate lawsuits or accusations of causing climate change through diligent (climate) compliance. Should companies, as a result of successful climate lawsuits, hold their managing directors liable for breaches of these duties, managing directors can probably invoke the business judgment rule, as they are granted broad entrepreneurial discretion with regard to the organisation of the company’s (climate) compliance system. This in turn means that managing directors should document the basis of their decisions on, for example, risk analysis, suspicions, and damage avoidance measures. This also applies to any recourse actions as a result of the company's liability in connection with breaches of due diligence in the supply chain, in particular under the new liability standard to be introduced by the CSDDD. In this respect, the managing directors must ensure adequate supply chain compliance, although the managing director will again be able to, in principle, invoke a discretionary scope in the implementation. In particular, there is a risk for companies – and, in the event of recourse claims, for the managing directors – that following violations in the supply chain, the damages asserted will be pursued through the newly introduced collective action for redress, which could potentially increase the asserted losses.

Summary and outlook

The liability risks for managing directors will therefore continue to increase in the coming years, which will also be noticed by D&O insurers. It will be all the more important for companies to have appropriate risk management in place to avoid ESG-related risks and damages, along with appropriate documentation of the information base and decision-making by managing directors. D&O insurers will therefore also have to further align their underwriting with the risks associated with ESG regulation and, in addition to a company‘s business model, thoroughly review.

[1] cf. Allianz Risk Barometer 2024, available at: https://commercial.allianz.com/content/dam/onemarketing/commercial/commercial/reports/Allianz-Risk-Barometer-2024.pdf.

[2] cf. Setzer J. and Higham C., Global Trends in Climate Change Litigation, 2023, available at: https://www.lse.ac.uk/granthaminstitute/wpcontent/uploads/2023/06/Global_trends_in_climate_change_litigation_2023_snapshot.pdf.

[3] Sabin Center for Climate Change Law Jurisdiction - Climate Change Litigation, available at: https://climatecasechart.com/non-us-case-category/corporations/).

[4] Regarding these or other decisions compare the article of Sven Förster, Karin Schäfer and Annalena Kienle in Clyde & Co‘s Quarterly Update Insurance 2/2024.

[5] German Federal Court of Justice, decision of 27 June 2024 – reference I ZR 98/23.

[6] Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation, Task Force on Nature Related Financial Disclosures, Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive, European Sustainability Reporting Standards, Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive.

[7] The following comments on the Green Claims Directive are partly verbatim and partly analogous to the article by Isabelle Kilian and Behrad Lalani in Clyde & Co‘s Quarterly Update Insurance 4/2023, but have been updated accordingly in view of developments in the meantime. The article in Quarterly Update 4/2023 was a second publication by the authors. The first publication was in VersPrax 9/September2023/Volume 113.

[8] German Federal Court of Justice, decision of 27 June 2024 – reference – I ZR 98/32.

[9] German Federal Court of Justice, decision of 27 June 2024 – reference – I ZR 98/32.

[10] See also the article by Sven Förster, Karin Schäfer and Annalena Kienle in Clyde & Co‘s Quarterly Update Insurance 2/2024.

End