Deter(mining) causation in South Africa: court orders Sasria to compensate insured over primary insurer

When may a South African court find that a director owes fiduciary duties to shareholders?

-

Legal Development 10 August 2022 10 August 2022

-

Africa

-

Insurance

More than 100 years ago the Salomon principle – that a company is distinct from its members – was laid down. A pillar of this principle is that the fiduciary duties of a director are owed to the company, not its shareholders. We discuss a recent case from the Johannesburg High Court which tests when a director’s fiduciary duties may be extended to shareholders.

The judgment of Ryan and Others vs Groenendaal and Others (12142/2022) [2022] ZAGPJHC 309 (13 April 2022) is available here.

Who’s who

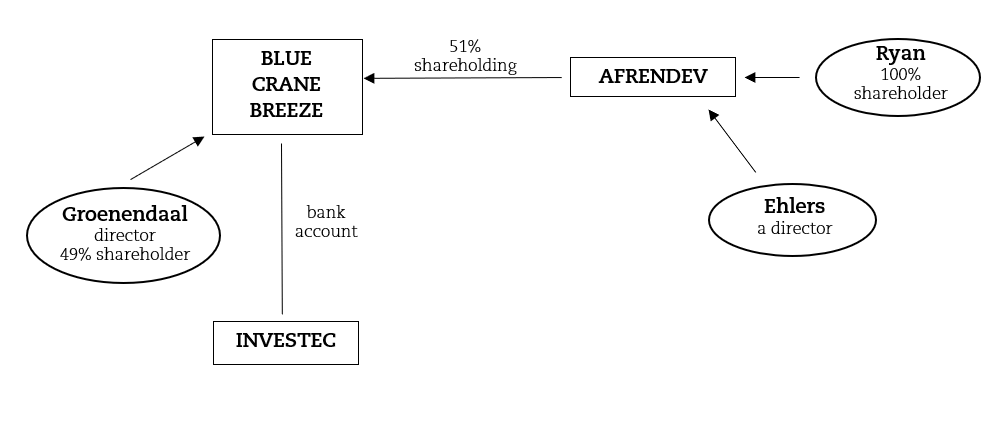

- Mr Groenendaal was the sole director and 49% shareholder of Blue Crane Breeze (Pty) Ltd.

- Blue Crane was a Special Purpose Vehicle (“SPV”) company that held a bank account with Investec Bank. It was incorporated for the specific purpose of exploiting opportunities in the Independent Power Production and renewable energy sector.

- Blue Crane was majority owned by Africa Renewable Development (Pty) Ltd or ‘Afrendev’. Afrendev held 51% of Blue Crane’s shares.

- Ms Ryan was the sole shareholder of Afrendev.

- Mr Ehlers was a director of Afrendev.

- The relationship between the parties is illustrated below:

The dispute

Ryan, Afrendev and Ehlers (“the Applicants”) brought an urgent application for an interdict that would afford them some control over Blue Crane’s bank account held with Investec.

Groenendaal instructed Investec to transfer all funds out of the Blue Crane bank account. Ryan and Groenendaal had previously been managing the account jointly and funds which Afrendev had loaned to Blue Crane formed part of the money in the account.

The Court had to consider (1) whether the Applicants had standing and (2) if so, whether they had a prima facie right to an interdict.

When may fiduciary duties be owed to shareholders?

Ordinarily, a director’s duties are to the company only. There is no general fiduciary duty owed to shareholders. A limited exception exists where there is a “special factual relationship” between the directors and shareholders, as described in De Bruyn v Steinhoff International Holdings NV and Others 2022 (1) SA 442 (GJ).

There is no closed list of special factual relationships, but Steinhoff offers some examples. A special factual relationship may exist where directors have persuaded outside shareholders to sell their shares in the company to the directors. In family companies where shareholders reposed trust and confidence in a family member and sought advice and information from them, a fiduciary duty was owed to those shareholders.

The court in Steinhoff explained that a special factual relationship will usually require a personal relationship with shareholders or some specific dealing between the directors and shareholders. Notably, the court in Steinhoff pointed out that Steinhoff was not a small company akin to a family business with closely held shares.

The special factual relationship in Ryan

The Court in Ryan distinguished the matter from the Steinhoff case. In Steinhoff the companies were JSE-listed, where regulation requires a segregation of duties of directors and shareholders. Blue Crane, in contrast, was a privately-held SPV with its shares held jointly by Groenendaal and Afrendev.

From inception, there had been an overlap in the roles of Blue Crane’s directors and shareholders. Ryan and Groenendaal were not elected directors. Instead, they were appointed in their “representative capacity as shareholders”. Their authority arose from their joint shareholding rather than the authority of an external body.

The dispute was categorised as a shareholder dispute. The bank account was managed by Ryan and Groenendaal in their capacity as shareholders, not directors. The management was by agreement and persisted even after Ryan resigned her directorship of Blue Crane.

The Court added that in the Supreme Court of Appeal case of Gihwala and others v Grancy Property Limited and others 2017 (2) SA 337 (SCA), the SCA stated that there is a “bond of trust” between shareholders and the directors they elect. The Court in Ryan held that Groenendaal, despite not being an elected director, owed a fiduciary duty to Blue Crane not to act to its detriment. The ‘bond of trust’ required that Groenendaal uphold earlier agreements, conduct and practices with shareholders.

The outcome

On the first issue, the existence of a special factual relationship, the risk and financial exposure to Afrendev, and other pending litigation between the parties were enough to satisfy the Court that the Applicants had standing.

Given the impending financial harm the Applicants would stand to suffer should money be transferred from the Investec account, the Court held that the Applicants had a prima facie right to an interdict. Ultimately, the Court ordered the reinstatement of the previous arrangement in terms of which both Ryan and Groenendaal managed the account.

Significance for directors

The particular relationship between these parties and the SPV nature of Blue Crane were enough for Judge Siwendu to extend a fiduciary duty from Blue Crane’s director to its shareholder. This is significant because, as discussed above, fiduciary duties are conventionally owed only to the company. The special factual relationship inquiry challenges that general principle and exposes directors to increased risk. Directors should carry out their roles with circumspection.

The Ryan case is representative of a subtle shift in public policy on the accountability of companies and directors. One of the benefits of incorporating a company is limited liability. A company’s separate legal personality ensures its directors and owners are not exposed to indeterminate liability.

Legally speaking, when we consider directors’ liability to a company and/or shareholders, we consider whether pure economic loss caused by the director’s actions is wrongful in law. The wrongfulness inquiry requires analysis of where the harm lies. Our courts have consistently held that the harm lies with the company and therefore it is the company, and not its shareholders, which is entitled to relief. Any loss that shareholders incur due to a decrease in share value consequent on directors’ actions is generally a consequence of harm done to the company itself.

Looking ahead, courts face the difficult task of striking a subtle balance between coming to the aid of shareholders who are deserving of relief, by virtue of a special factual relationship with directors, and the fundamental tenet of company law that a company enjoys separate legal personality and limited liability.

For more information regarding these judgments and their impact, please contact a member of the team at Clyde & Co.

End