Banks and insurers have more work to do on climate risk: The Bank of England publishes the results of its Climate Biennial Exploratory Scenario

-

Insight Article 31 May 2022 31 May 2022

-

UK & Europe

-

Climate change

-

Climate Change Risk Practice

The Bank of England publishes the results of its Climate Biennial Exploratory Scenario

Since 2015, the Bank of England has been part of a global regulatory movement spearheaded by the Financial Stability Board seeking to address the “tragedy of the horizon” of climate change related financial risks. The Bank’s expectations were set out in its Supervisory Statement 3/19 and a Dear CEO letter dated 1 July 2020. The Bank expects regulated firms to:

- embed climate risks in business-as-usual risk management

- engage counterparties to understand their vulnerability to climate change

- encourage boards to take a strategic, long‑term approach to managing these risks

On 24 May 2022 the Bank of England published the results of its Biennial Exploratory Scenario focused on financial risks from climate change: the Climate Biennial Exploratory Scenario or “CBES”.

The CBES scenarios were designed to explore the vulnerability of current business models to future climate policy and global warming pathways, and ascertain how participating firms intend to adapt business models over time. CBES findings are intended to support the Bank in its role as a primary lever for driving an orderly economy-wide transition to net-zero emissions.

What is CBES?

The Bank of England runs two types of regular stress tests to assess the resilience of the UK financial system.

- annual solvency stress tests; and

- biennial exploratory scenarios (BES).

The objective of the inaugural Climate BES was to explore the financial risks posed by climate change for the largest UK banks, life insurers and general insurers. The following were selected as participants:

- Banks: Barclays, HSBC, Lloyds, Nationwide, NatWest, Santander, Standard Chartered

- Life insurers: Aviva, Legal & General, M&G, Phoenix, Scottish Widows

- General insurers: AIG, Allianz, Aviva, AXA, Direct Line, RSA, and Lloyd’s (ten selected managing agents)

What were the scenarios?

CBES used three scenarios for a plausible representation of what might happen from 2021 to 2050 to explore two key risks from climate change:

- Transition Risks: the risks that arise as the economy moves from a carbon-intensive one to net zero emissions; and

- Physical Risks: risks associated with the higher global temperatures likely to result from taking no further policy action.

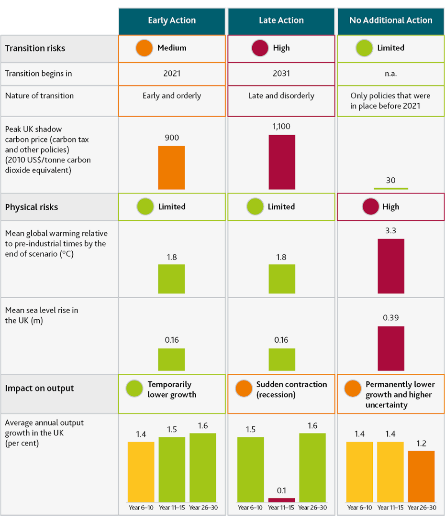

The scenarios considered three possible action pathways (infographic below):

- Early action:

- net-zero transition begins in earnest in 2021

- CO2 reduced to net-zero by 2050

- Global warming limited to 1.8 degrees by 2050

- Late action

- Concerted net-zero policy action delayed until 2031, resulting in material short-term macroeconomic disruption concentrated in carbon-intensive sectors

- Global warming limited to 1.8 degrees by 2050

- No additional action

- No new climate policies introduced, growing GHG emissions in the atmosphere, and severe impacts on extreme weather, ecosystems and sea-level

- Global warming of 3.3 degrees by 2050

These were based on a subset of climate scenarios developed by the Network for Greening the Financial System, an international body bringing together 114 financial regulators globally.

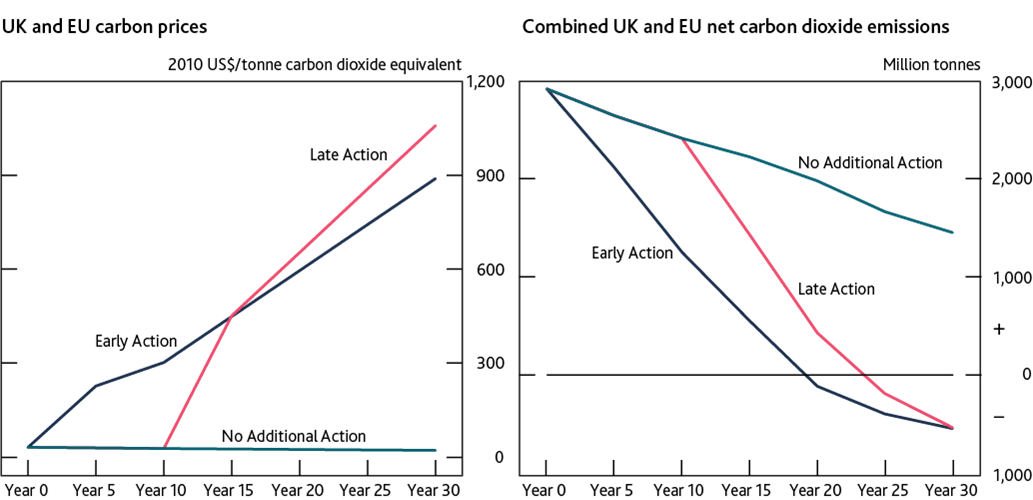

Transition risk

A carbon price was used as an indicator of the level of transition risk. In the Early Action scenario, carbon prices were expected to increase from roughly US$30 per tonne to just under US$900 by 2050 in the UK and EU. In the Late Action scenario, carbon prices would remain at US$30 until 2030, and then rise steeply to over US$1,000 in 2050. In the No Additional Action scenario, carbon prices would not rise.

Physical risks

Global mean temperatures have already increased by around 1.1°C from pre-industrial levels. In the Early and Late Action scenarios, global warming reaches 1.8°C by 2050, falling from this peak in the latter part of the century. In the No Additional Action scenario, global warming relative to pre-industrial times reaches 3.3°C by 2050.

Change in global warming levels relative to pre-industrial times

| (˚C) | Year 0 | Year 10 | Year 30 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early and Late Action scenarios (a) | 1.1 | 1.4 | 1.8 |

| No Additional Action scenario (b) | 1.1 | 2.5 | 3.3 |

Climate litigation and general insurers: hypothetical cases

CBES also included a template for general insurers to explore potential exposures to climate-related litigation risk. General insurers were asked to provide details of their exposure (policy limits and probable maximum loss) from specific products, in-force on 31 December 2020, covering various sectors of the economy that have been identified as having an elevated or direct exposure to climate risk.

The scenario provided a number of hypothetical legal case rulings against insureds to assess the potential risks arising from climate litigation, inspired by actual civil cases, with 7 sample cases:

- Direct causal contribution: a corporate found liable for contribution climate change resulting in physical damages

- Violation of fundamental rights resulting in cessation or significant reduction of operations: corporate prevented from practicing carbon-intensive activities impacting its financial revenues (stranded assets)

- Greenwashing: corporate liable for misleading customers and investors by false advertising or understated climate risk disclosures

- Misreading the transition: corporate liable for selling a carbon-intensive product with the knowledge it would become redundant in view of net-zero policies

- Indirect causal contribution by utilities: utilities sued for indirect contribution to climate change amplifying physical risks

- Directors’ breach of fiduciary duties (asset managers): case brought by investors of an asset manager relating to breach of directors’ duties due to understatement of risk in disclosures

- Indirect causal contribution (financing): case against financiers of carbon-intensive activities by funding activities of carbon majors

The parallels between these and actual cases in the Courts are clear to anyone familiar with the growing body of climate litigation globally. To learn more about climate liability risk see our 2021 publication Climate change litigation with the Geneva Association and London School of Economics Grantham Centre.

What were participants required to do?

Participants were asked to measure the impact of the scenarios on their end-2020 balance sheets, as a proxy for their current business models, and to explore how they might change business models to mitigate risk (so-called “management actions”):

- For banks, CBES focussed on the credit risk associated with the banking book.

- For insurers, CBES was focussed on changes in: (a) Invested Assets (and Reinsurance Recoverables); and (b) Insurance Liabilities (including accepted Reinsurance) assuming an instantaneous shock (with no allowance for changes in future premiums, asset allocation, expenses, reinsurance programmes and other future changes in participants’ business models).

From its launch in June 2021 participating firms worked through a qualitative questionnaire and data templates set out by the Bank. Firms’ climate risk management capabilities were assessed based on their CBES qualitative questionnaire responses covering several aspects of their approach to climate risk, including overall strategy, risk management and modelling approaches. Firms also submitted prospective management actions, exploring how they might change business models. The Bank launched a second round of CBES in February 2022 to explore the prospective responses in greater depth. In Round 2 CBES participants were asked inter alia to provide further detail about the opportunities they would seek to exploit, assume that losses would be double their initial central projections, and djudge the credibility of counterparties’ net-zero transition plans.

What was the result?

The Bank has now published the aggregated CBES results, but has not disclosed the results of individual firms, in keeping with its systems-level approach and analysis. The Bank will give firm-specific feedback to participants, and will use findings from the CBES to help target their efforts.

Key findings include:

For insurers, the No Additional Action scenario would have a more significant impact than either the Late Action or Early Action scenarios. For life insurers, this was because forward-looking asset price impacts are greatest at the end of that scenario. For general insurers, losses would stem from a build-up in physical risks, which resulted in higher claims for perils such as flood and wind damage.

Banks and insurers have made good progress but need to do much more to manage climate risk: participants lacked data on key factors needed to understand climate risk, such as corporates’ current emissions and future transition plans.

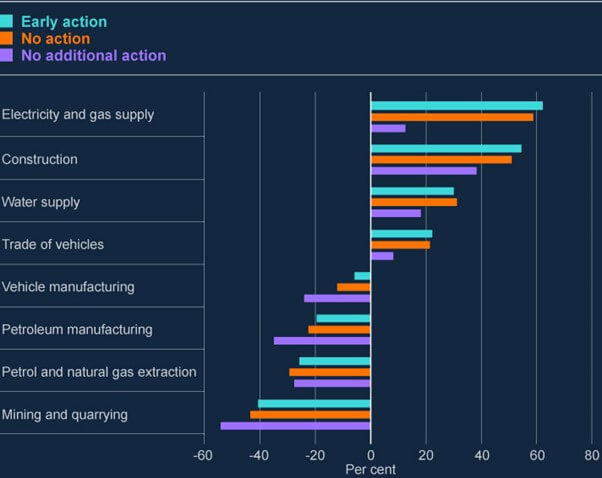

Collectively, banks and insurers net-zero plans could impact the wider economy: Banks and insurers reported plans to reduce their exposure to carbon-intensive sectors, with banks projecting large reductions in exposure to the petroleum & gas extraction, petroleum manufacturing, and mining & quarrying sectors. These strategies raise the possibility that some corporate sectors (particularly some carbon-intensive ones) may struggle to access finance as the transition progresses, especially from banks. If the transition is not managed carefully and limits on lending and insurance to corporates in carbon-intensive industries run ahead of renewable energy and energy efficiency there could be significant economic impacts on businesses, consumers and through them the entire financial sector.

(a) Indicative net change in drawn balance from year 0 to year 30 based on firms' submissions, abstracting from the impact of underlying trends in growth and inflation over the scenario. The Cchart shows sectors for which banks submitted the largest changes in drawn balances. All banks quantified potential reductions in exposure in response to the CBES scenarios, though some did not quantify potential increases

Climate liability risk

Firms’ responses to the CBES exercise’s climate litigation scenarios revealed that they struggled with collating and aggregating information for a robust assessment of climate-related litigation exposures according to contract wording and industry sector classifications.

Examples of best practice included:

- Using a multidisciplinary team (underwriters, claims handlers, legal, risk management, actuarial)

- Submitting initial results to robust internal challenge

- Considering a wide range of legal interpretations

- Using findings to inform existing risk manage practices

- Applying technical rigour in considering policy exposures (e.g. risk differentiation within sub-sectors, consideration of differing geographical and legislative environments)

The exercise highlighted that corporate D&O policies were the most likely to pay out and were vulnerable to three of the seven hypothetical legal cases. PI policies were also at risk from the indirect financing case. Participating insurers noted that they also covered legal defence costs, meaning that costs could be sizeable even if litigation against insureds is unsuccessful.

Why does CBES matter?

The Bank described CBES as a “learning exercise”, noting that expertise of modelling climate-related risks remains in its infancy. Specific work is now being done between the Bank and participants on a confidential basis. The Bank will use the results to assess the participants’ progress against its expectations in this area (set out in SS3/19). CBES will also feed into the work of the Bank in a supervisory role and so is important for other regulated entities who didn’t participate, through individual supervisory dialogue and discussing key findings with industry (including through the Climate Financial Risk Forum (CFRF)).

CBES will almost certainly feed into future regulation. Participants’ submissions may inform the Financial Policy Committee’s (FPC’s) approach to system-wide policy issues and the Prudential Regulation Authority’s (PRA’s) approach to supervisory policy.

As described in the PRA’s 2021 Climate Adaptation Report, from January 2022 the PRA started to supervise firms actively against the expectations set out in SS3/19. Climate change will become part of the PRA’s core supervisory process, with the assessment of climate-related financial risks included in all relevant elements of the supervisory cycle. CBES will feed into that assessment. Firms judged not to have made sufficient progress in embedding the PRA’s expectations will need to provide a roadmap to explain how they will overcome the gaps.

By the end of 2022 the PRA intends to provide updates on:

- whether changes to the regulatory capital regimes are necessary to address climate risk

- whether regular data on climate risk will be required via regulatory returns

- further plans for climate scenario analysis

- considering disclosures on transition plans which may be required as part of proposed Sustainability Disclosure Requirements (see: Greening Finance: A Roadmap to Sustainable Investing - GOV.UK (www.gov.uk) and DP21/4: Sustainability Disclosure Requirements (SDR) and investment labels (fca.org.uk))

As with many aspects of climate risk governance and supervision, the UK has taken a leading role globally, so it is inevitable that the CBES exercise itself or its results will feed into the global financial supervisory response through:

- Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS)

- International Association of Insurance Supervisors (IAIS)

- Sustainable Insurance Forum (SIF)

- Financial Stability Board (FSB)

In sum, this isn’t the end of the journey, but the beginning for many banks and insurers in the UK and internationally.

Next steps – key action points

The CBES exercise is one part of the UK government’s pivot towards a climate-resilient economy. Importantly, it is not just the first participants in CBES, but other market participants, and those they insure and finance, which need to be aware of what is happening from a regulatory and supervisory point of view. As part of their ongoing climate risk management, companies and their advisors can:

- Consider the CBES scenarios and results of the exercise published by the Bank of England, particularly the best practice which for insurers includes:

- Using bespoke modelling approaches for sectors with specific climate vulnerabilities

- Adjusting pricing models to account for the fact that future changes in physical or transition risks may affect market prices in the near-term

- Modelling a wide range of physical perils, beyond the most readily available catastrophe models

- Reviewing academic research to inform physical risk modelling

- Demonstrating validation and review of results of physical risk modelling by comparing them to alternative models and through engage with internal and external specialists

- Insurers may also wish to consider:

- including climate scenarios in stress and scenario tests included in Own Risk and Solvency Assessment (ORSA) reports

- setting target dates for investment portfolios to be net-zero and tracking current portfolios against those targets

- setting qualitative or quantitative risk appetites for underwriting activities

- seeking third party modelling support or developing in-house capability

- gathering data on companies’ emissions and geographical locations of supply chains

- For participant firms – continue to engage actively with the PRA on next steps, identifying gaps and establishing appropriate internal review and action or professional advisory support to address concerns

- For non-participant firms – consider existing supervisory requirements under SS3/19 and consider preparing the business by reference to CBES and its results on best practice

- Keep abreast of the work of the Bank of England and PRA as well as the NGFS, IAIS, SIF, and FSB in this area

- Actively engage with any relevant disclosure regimes (TCFD, ISSB, CDP, etc)

- Keep abreast of the development of the Sustainability Disclosure Requirements, in particular as regards transition plans.

End